In today’s episode, we are going to take a look at the future of warfare. This is a request I received from a listener and here’s the nice thing about listening to a podcast with a modest audience: if you ask for something there’s a good chance you’ll get it!

We are going to weave into this discussion an update on Ukraine, because I also got a request to do that and, for now, this podcast is something of an egalitarian paradise so everyone gets what they want. Well, sort of. Ukraine is actually a great jumping off point for a discussion of warfare because we have seen a lot of developments on that battlefield that provide clues about where warfare is going, but also frankly show us aspects of warfare that appear to be somewhat immutable.

Ukraine

Ok, so where are the poor old Ukrainians at these days? I'm not going to sugar coat it - the situation is grim. Before we get into where things might go, I think it's helpful to recap where we've been. Apologies in advance to regular listeners for whom this is all familiar ground.

So Russia invades Ukraine in February 2022, just over two years ago. The Russian plan was to launch a swift decapitation strike against the Ukrainian leadership that would paralyze national decision making and enable Russian forces to march across the country largely unopposed. Russia then planned to install a pro-Russian regime and turn Ukraine into a Russian client and subsequently withdraw its forces.

Instead, the Russian invasion quickly turned into a farce. While Russia did capture significant territory in the opening weeks of the war, ultimately Ukraine was able to stabilize its lines and inflict significant casualties on Russian forces. Russia's most spectacular failure was the stalling of a column of armored vehicles trying to break through to Kyiv. This column ended up effectively in a traffic jam which allowed Ukrainian troops armed with Western anti-tank missile systems to pick off vehicles at will.

The Russian offensive quickly petered out and the conflict settled into an attritional fight. In the north, around Kharkiv, Ukraine was able over time to attrit Russian forces to the point that Ukraine launched a successful counterattack in the region in late 2022 which regained hundreds of kilometers of territory. Ukraine made gains in the south as well.

In the late winter and spring of 2023, Ukraine constituted about nine new brigades or about 30-40,000 troops. These brigades were equipped with modern Western equipment especially tanks, infantry fighting vehicles and breaching equipment. They also received training from Western officers in what is called combined arms maneuver. The basic idea was that these Ukrainian brigades would achieve a breakthrough somewhere in the Russian line, and then maneuver around much of the prepared fortifications the Russians had deployed which included multiple lines of trenches, some lined with cement, and extensive minefields.

That offensive failed due to a combination of factors but most important were the following. First, the combined arms tactics pushed by the West conflicted with the doctrine already in place within the Ukrainian army. As I've mentioned, the West fights on the basis of combined arms maneuver. Ukraine's military, which remains heavily influenced by its many decade experience of being an appendage of the Soviet Red Army, has a doctrine much more oriented arounds "fires" or artillery. It is through artillery and destroying the enemy that you earn the right to maneuver. So, in summary, the West was trying to teach an old dog new tricks which might be fine, but perhaps not in the middle of a war. You want the old dog to learn and practice those skills in a less high pressure environment.

The second reason for the failure was that the brigades equipped were made up primarily of new personnel. Instead of trying to train Ukraine's most experienced soldiers on these new tactics, the West delivered the training and equipment to Ukraine's least experienced personnel. In hindsight, I think that's a choice that everyone wishes they could have back. Ukraine's more experienced and battle hardened units performed better during the counter offensive even without advanced Western equipment which suggests their gains might have been even greater with better gear.

I think this is one of those decisions which, while we now know was probably incorrect with hindsight, seemed pretty reasonable at the time. If you are going to teach new tactics, I can understand why someone would conclude it's better to teach new recruits than to try to teach soldiers potentially stuck in their ways.

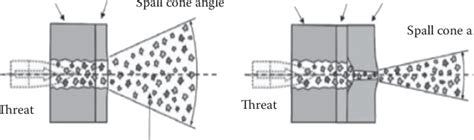

The third factor that undermined the offensive was the fact that Western equipment, while superior to Russian equipment, simply was not decisive when it came to breaching Russia's prepared defenses. The main thing that Western vehicles do much, much better than Russian ones is keep the crew alive. You're probably wondering how so let me give you one example: the spall liner. When an anti-tank weapon hits an armored vehicle, often part of what it is trying to do is to create "spall" inside of the vehicle. Spall is all of the fragments released by an object when it is subjected to a powerful force. What anti-tank weapons are trying to do is hit the metal wall of an armored vehicle, fragment it, and then send those fragments flying around the interior at high speed and hopefully kill the crew.

A spall liner drastically reduces the dispersion of spall inside an armored vehicle so that it hits fewer crew members. I've included a graphic below to show what I mean.

I should clarify that some Russian vehicles probably use spall liners and other life-saving devices. But just nowhere near the same extent as Western and especially American vehicles. Anyway, this is obviously not enough to provide an edge over the prepared defenses that I've mentioned here many times in the past.

It is worth noting that while Ukraine's ground offensive failed, it had multiple success against the Russian Black Sea fleet, based on the Crimean Peninsula, in 2023. This was significant because it pushed those vessels away from Ukrainian ports and allowed Ukrainian exports to slip the Russian naval blockade and provide vital commerce to the Ukrainian economy. But really, this was the only bright spot for Ukraine last year.

As 2023 came to a close, a new threat for Ukraine emerged which was and remains the refusal of the US Republican Party to continue underwriting Ukraine's war effort in terms of military equipment. The US has been, by far, Ukraine's largest benefactor with respect to military hardware. The main reason that Republicans oppose further aid to Ukraine is that former President Donald Trump continues to bear that country ill will for failing to unearth the dirt he believed existed that showed a massive conspiracy of corruption related to the Biden family. This was actually the cause of his first impeachment: Trump made military assistance and a White House invitation for President Zelenskyy conditional on Ukraine finding this imagined evidence. We now know that entire issue was actually the production of Russian intelligence services which fed the false conspiracy theory to Trump and his inner circle by a now busted informant. Trump continues to bear ill-will toward Ukraine out of all of this hence his orders to the Republican party to oppose further Ukraine aid.

The stated reason provided by Republicans for withholding Ukraine aid is that the US has provided enough already and it should be Europe's job to deliver security on that continent's far eastern fringes / its border with Russia. Notwithstanding the bad faith motivation for making this argument, it does have some validity worth engaging with on its own merits. JD Vance, one of many Trump allies who was against him before he was for him, made a compelling argument on this in the Financial Times. His most compelling point was to ask whether decades of US security guarantees had led Europe to under invest in its own security and to leave itself poorly defended.

The cornerstone of European defense and security is NATO which is short for the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. Formed after World War 2, NATO's primary purpose was to act as a counterweight to the threat of Soviet aggression against Europe. It comprised the US and most of the major states in Western Europe and after the Soviet Union collapsed it crept further eastward as more and more European states, fearing Russian aggression, sought shelter in NATO's collective defense doctrine. What's meant by collective defense is that an attack on one NATO country will be treated as an attack on all of them to trigger a massive retaliatory effort as a way of discouraging an invasion in the first place.

Among other provisions, the NATO treaty calls on member states to spend at least 2 percent of their GDP on defense. Many European nations have been falling below that mark for decades and Vance's point is that the US, by allowing them to do so year after year, has enabled Europe to become complacent about its own defense. And, frankly, he has a point here. Europe has still declined to make the serious investments that would be required to ramp up its production of artillery ammunition to give Ukraine at least parity in the fires contest and we're more than two years into this war. You will often read stories or hear on pods that Russia is ramping up its military production so that it can overmatch Ukraine in the artillery war. What these comments often leave out or fail to make clear is that if Western Europe wanted to, it could easily match and exceed Russian military production. European manufacturing is far more sophisticated and capable than Russia's manufacturing base. But to do this, European nations need to submit orders for ammunition from the private sector so that they will make the necessary investments. But they haven't done so and they continue to decline to do so.

This is absolutely extraordinary given that, if Putin is victorious in Ukraine, the idea he will stop there is both ridiculous and naïve. So, back to Vance's point, Europe really ought to shoulder more of the burden of funding collective defense. Personally, I don't think the time to make that argument is while Ukraine, which could blossom into a key partner of the West and a further bulwark against Russia, is fighting for its life. Instead the US should have gotten serious about NATO funding under any of the Trump, Obama, Bush, Clinton or Bush again administrations.

So… What was the point I was making? Nah come on, I remember. The point I was making was that US support is rapidly drying up for Ukraine, and as we just discussed, European support isn't really where it needs to be to bridge the gap. On top of that, you are starting to see concerning signs of divergence in the domestic political scene. In early February, Zelenskyy fired Russia's top general, Valerii Zaluzhnyi. Zaluzhnyi is probably the most popular person in Ukraine because he is seen as the architect of Ukraine's initial defense against the Russian invasion and its subsequent counter offensive in late 2022 which gave Ukrainians so much hope. However, various points of strain had emerged between he and Zelenskyy.

First was obviously the failure of the 2023 counter offensive which couldn't have made for the most pleasant conversations between the two of them. Then in November of 2023 Zaluzhnyi acknowledged in an interview that the war had reached a point of stalemate. This was a perfectly fair observation of the situation but did not align with the message Zelenskyy wanted to project domestically. Recall that he has promised Ukrainians total victory and the restoration not just of Ukraine's borders on 2022 lines, but 2014 lines when Russia annexed Crimea. And, finally, you have the fact of Zaluzhnyi's popularity itself. This makes him a political threat to Zelenskyy as Zaluzhnyi is frequently cited as a potential challenger to Zelenskyy in an election setting.

This is not the only area in which domestic political considerations are going to influence Ukraine's prospects for victory. On average, men serving in Ukraine's armed forces are in their early 40s. That is simply not a good age at which to be fighting intense battles in close quarters. It just isn't. The fact is that despite all the advances in technology over the last one hundred years of warfare, high intensity assaults are best fought by much younger men.

This raises the question: why doesn't Ukraine implement a draft to bring in a younger layer of soldiers? The reason is that Ukraine has an incredibly imbalanced demographic profile: there are many more Ukrainian men in their late 30s and 40s than there are in their 20s and so drafting a bunch of 20 year olds is seen as compromising Ukraine's demographic future. Ukrainian businesses are also wary of doing this because they don’t want to see workers drawn out of the labor force. It is, of course, easy to judge Ukrainians for their choices from afar. But it is nevertheless true to say that Ukraine faces a much, much better prospect of victory in this war, which presumably its entire populace wants, if it is able to generate more manpower to combat Russia.

Putting all of this together, you can understand why Putin is probably feeling quite confident as 2024 gets started. Ukraine's forces will be starved of ammunition and manpower, and the theory of victory he has been articulating to the Russian people, that the West will get tired and bored, appears to be bearing out exactly as he predicted. Realistically, the best Ukraine can hope for and what it should focus on is holding its current territory while it improves its ability to fight the war from a logistical standpoint. Ukraine needs to be able to train and equip more men, and it needs to be able to supply them with more ammunition, especially artillery ammunition. And while it will not be politically popular, Ukraine needs to start digging in and fortifying its positions so that if Putin makes a move sparked from over confidence, like attempting a similar offensive set of maneuvers that opened the war back in 2022, Ukraine is in a position to capitalize and inflict maximum casualties on Russian forces.

This time last year, Ukrainian forces were buoyant after their lighting counter offensive of late 2022. 2024 is going to be a real test of the country's ability to sustain a long, drawn out war and to make the really gut wrenching, painful decisions that will be required if Ukraine is to emerge victorious.

The future of warfare

Alright, phew, that ended up being a longer section on Ukraine than I anticipated. But now let's get into the future of warfare stuff by starting with some of the developments we've seen on the battlefield in Ukraine that have people really sitting down and wondering where all this is headed. The first is the role of drones which have created unique dynamics on the battlefield in at least two ways. The first is that drones now provide both sides with ubiquitous, permanent surveillance of the front. This creates all kinds of problems. One problem it throws up is how to achieve concentration of forces for an assault? As you gather all of your assault forces in one place, this action is likely to be spotted and the drone can be used to quickly target precise artillery fire against the assembling units.

An interesting side note, I have read that drone surveillance created situations where it was easier for troops to move at daytime. The reason being that for drones equipped with infrared cameras, it is extremely easy to see soldiers because they stand out against the cold background. But when forced into standard video, they can actually be harder to see. I didn't have the forethought to save the source for this observation so apologies for that.

The second dynamic drones have created is to dramatically expand and disperse the capability for precision strike at multiple levels of warfare. From a strategic point of view, Ukraine is ramping up a domestic capability to build long range drones capable of striking targets deep in Russian territory. Ukraine sees this as a key need so that they can bring the war home to the Russian people and increase the domestic costs paid by Putin for prolonging the war. This is not a capability that Ukraine otherwise has or would have.

Probably more impactful, and certainly more widespread, is the relationship between drones and precision strike at the tactical level. There are thousands of videos on YouTube showing drones from both sides dropping mortar rounds or grenades into fox holes, or onto soldiers or even through the open roofs of tanks and armored vehicles. Increasingly, both sides are relying on first person view or FPV drones. These drones are operate by someone wearing virtual reality glasses or goggles and can fly right up to a target at which time they are detonated. Rather than operating as a separate unit with which some kind of coordination would be required, such as artillery, front line units frequently have their own drone operators allowing them to deliver precision strikes without further coordination.

As a result of drones' strike capabilities, people are beginning to ask questions like what is the point of a tank, which costs several million dollars, if it can be destroyed by a few drones costing tens of thousands? Or consider Russia's Black Sea Fleet which has been decimated by underwater and surface-based drones. Those ships cost hundreds of millions of dollars to design and build and several of them were sunk by drones that cost a fraction of that. Put another way, is the future of warfare one that will be dominated by a few, big and expensive systems? Or one dominated by dispersed swarms of very cheap systems?

This isn't the only big, meaty question on the table. What is the role of gaining and holding territory, for example? In an age of tanks, infantry fighting vehicles and aircraft, the war in Ukraine has settled into a trench-based stalemate with strong parallels to the First World War - how can this be?

As with most things, I think it's always helpful to know where we have been to have a sense of where we might be going. So even though you came for the future of warfare, we're going to spend some time with the history of warfare.

I will do my best to give you the headlines here but let me stress that there are many, many books about this topic. There are professional academics who make entire careers out of their knowledge of different formations used by Roman legions, or whatever. So when I say these are the headlines, I mean they really, really are the headlines.

To make things manageable, I am going to heavily summarize everything up until about the 17th century. There are a few major aspects to warfare to note during this period which spans antiquity all the way up to the late Renaissance. The first is that it was primarily hand-to-hand combat. Ranged weapons existed, such as the bow and arrow/crossbow, but these were still line-of-sight weapons. You had to see what you were aiming at. And large ranged weapons like trebuchets, catapults and ballistas were mostly used for siege purposes. For most of human history, warfare was an up close and personal affair.

The second critical aspect related to warfare prior to the 16th century is that much of it was undertaken by citizen-soldiers. In other words, they were often not professionals. There are of course significant exceptions. The Roman legions are probably the most famous example, but there are others such as the Immortals of the Achaemenid Persian Empire and components of the Mongol Army. But part of the reason these examples stand out is because they were professional fighting forces in a time when most fighting was done by amateurs. Typically this occurred in a feudal arrangement whereby landed nobles owed a certain number of soldiers to their overlord in times of war, and they would draw those soldiers from the peasants who worked their land. Those peasants were obviously not professional soldiers. So that was a major change we will dive into.

The third aspect of pre-17th century warfare is that there really was quite limited operational-level maneuver. Sure, there was maneuvering of various formations and such on the battlefield. But what I mean is that combat mostly consisted of pitched battles. The contesting armies lined up in front of one another and charged. The cavalry might move first. And the commanding general might choose to advance one side of their line over the other, but ultimately both armies were looking to come to grips with one another directly. The idea of maneuvering around your enemy was not the primary goal: it was to kill as many of them as possible.

Many people assume the arrival of gunpowder changed everything about warfare. Over the long-term, this is true. But it didn't happen right away. Invented in China, the earliest reference to gunpowder dates to 142 AD. It didn't spread to Europe until the 13th century when it was introduced by Mongol invaders. Eventually, the fierce competition among small, relatively densely populated European states would see them pull far ahead of every other part of the world in terms of using firearms and this would be a critical factor in Europe's imperial expansion across the world between the 18th and 19th centuries.

But as late as the American Civil War in the 1860s, armies still fought relatively pitched battles. Soldiers lined up in rows and fired their weapons at one another and whoever killed more of the enemy won. That's an oversimplification, but not by much. Let's take a quick detour to understand why battles still had to be fought that way so recently in human history. In many ways it comes down to physics. There are two ways to stabilize a projectile's flight through the air to make sure it has a good chance of hitting whatever you're aiming at. One way is fin-stabilization. That's why missiles have fins on them, to keep them steady and stable as they fly through the air. Another, less effective way, is to spin stabilize the projectile. Basically, when you set a projectile spinning on its longitudinal axis, the axis that goes from the back to the front, that helps preserve the projectile's angle. Ultimately gravity will take charge and cause the projectile to drop, but spin stabilization provides much more accuracy than the alternative, which is no stabilization.

And that brings us to why, even with firearms, soldiers still had to line up and shoot at one another. Until the American Civil War, most firearms had what's called a smooth bore. In other words, the inside of the barrel was just a smooth piece of metal. During the early 1800s, military engineers started experimenting with rifling the barrel. Rifling is where you put grooves in the barrel so as the projectile travels down it, it is forced to spin and you get spin stabilization. The inaccuracy of smoothbore weapons meant that your only bet for achieving concentrated fire on the enemy was to concentrate your own forces and have them shoot at one another. During the American Civil War there was widespread movement from smoothbore firearms or muskets, to rifles and by the start of the 20th century all modern militaries were arming their infantrymen with rifles.

Ok so that was quite the detour on rifling. Alright gunpowder arrives but, at least initially, it's not that big a deal. What was the big deal then, in the 17th century? The big change that starts happening around this time is that warfare transitions from being fought primarily by citizen-soldiers, amateurs, part-timers etc., to being fought by professionals. You go from armies that convened in an ad hoc fashion in times of war, to standing armies comprising full time soldiers who were paid a steady wage to be part of the military in peace time and in war time. A key figure in this development was the King of Sweden in the early 1600s, a bloke by the name of Gustavus Adolphus. Strong name although that old Adolphus part perhaps why he is not well known.

Anyway, Gustavus did a lot to professionalize the Swedish military, innovations that other European nations would be forced to copy. In some ways you can summarize his central insight as being that when you are paying a standing army, you can get them to do a bunch of things that part-time soldiers either can't or won't do. And these three things are dig, drill and die. With regard to digging, Gustavus ensured that his armies were capable of defending from prepared positions which are much more effective than defending without preparation. But prior to professionalization, citizen armies often had at the head of them the aristocracy or nobility. Good luck getting them to dig.

Drill was critical to executing maneuvers against the enemy. To be able to move large formations of men in a synchronized fashion requires practice. But when the bulk of your army is off tending to the farm, you can't drill. Hence, you needed a standing army.

And, finally, to die. This seems obvious when talking about armies but the reality is that having standing armies bred camaraderie between the troops which changed things to some degree. When you had part time soldiers coming together, it was usually because of some obligation to a feudal overlord. Not exactly the most inspiring basis on which to demonstrate bravery and to give the ultimate sacrifice in battle with the enemy. But with a professional army full of soldiers who trained together and had survived prior battles together, the potential to build morale and mutual dependence in terms of standing firm in the face of enemy attacks increases.

These weren't Gustavus' only big contributions to changes in warfare. He was one of the earliest proponents of combined arms warfare, stitching together infantry, cavalry and artillery in a combined battleplan. He spent a lot of time thinking about mobility and speed with a focus on how to make artillery lighter and more maneuverable so it could be deployed at the most critical points of the battle. But his contribution to professionalization of military forces was, I think, his most important contribution.

You may wonder, why was it at this time that military forces started to professionalize? I don't have a great answer for that but I can speculate. As I mentioned earlier, Europe stood apart from much of the rest of the world in having these relatively advanced but small nations all close together which fueled military competition and innovation. But also happening in this period was the refinement and development of today what we would call the "state" or perhaps the "government". The powers of bureaucracy were increasingly starting to centralize. Kings were giving up power to early forms of parliaments in exchange for those parliaments funding their wars. These growing bureaucracies and the willingness of parliaments to trade taxation rights for political rights (I'm simplifying) meant suddenly the resources were available to pay standing armies. In an era of constant military competition, that's a no brainer. Anyway, that's my theory and I'm sticking with it.

Ok so we had professionalization starting in the early 17th century. And all of the trends and developments it kicks off continue to develop in a pretty linear fashion. Artillery gets better. Armies train more and learn new stuff, and so on. The next big step change in how wars were fought comes in the late 1700s to the early 1800s. And they are mostly thanks to a little fella whom today we know as Napoleon. I am not a huge Napoleon buff, but I will tell you I found the recent Ridley Scott film about him a bit disappointing. The film focuses pretty heavily on his relationship with his wife, Josephine, and it seems to imply that all of Napoleon's conquests and achievements were all in service of impressing her. Which may well be true of Napoleon's psychology, but it does mean the audience comes away thinking he was a guy who basically just tried to impress a girl. And maybe that's true and that was really everything behind his actions. But it does obscure somewhat just how drastically he remade his corner of the world.

Anyway, you didn't come here for my movie criticism. Let's talk about some of Napoleon's legacies when it comes to how wars were fought. The first concept I'm going to talk about actually pre-dated Napoleon's rule over France, but it was his battlefield successes that showed how important it would be going forward, so I'm lumping it in with him. Pardon the sleight of hand. Anyway, the concept I am referring to is called levee en masse which in English means mass national conscription. The French Revolution, which toppled the French nobility, shook Europe to its foundations. Across the continent, the old monarchies saw how they might be swept from power by popular uprising of the masses and they knew that their own people saw that too.

As the Revolution became more radical, and more and more of the French elite had their heads cut off by the guillotine, the other great powers of Europe couldn't stand by any longer and war eventually broke out. The details are not important for our discussion but ultimately France found itself in a war against several of the other Great Powers of Europe: Great Britain; the Holy Roman Empire; Prussia, which would ultimately go on to form Germany; and a host of other second-tier powers including Spain, Portugal and the Papal States.

To confront such a significant array of manpower, France implemented conscription at a massive scale. In the context of the war, it was a massive success. France ultimately defeated the combined powers of Europe, preserving the newly independent republic. But more importantly for this discussion, Revolutionary France had shown what was possible in terms of moving an entire nation to war footing. By turning out a huge amount of its population, France was able to defeat the combined forces of much of Europe and this would change warfare forever, at least between major powers. Going forward, being able to fight and win a major war would be about more than just having a well-trained, well-equipped standing army, the national capacity for war would matter too. And not just in terms of manpower and being able to draft conscripts into the armed forces, but also the capacity to clothe, feed and above all, arm them. This transformation of warfare from being primarily between armies to between nations would make it much more all-encompassing and destructive because of the huge amount of manpower and economic capacity that would be invested in warfare moving forward.

The next major innovation brought forth during this period is much more closely identified with Napoleon and it involves military organization. Napoleon invested a lot of time and energy into re-organizing the French Army from the ground up in a way that enabled it to be decomposed into smaller and smaller units. What this allowed Napoleon to do was to break off pieces of larger formations, when he needed them, and redeploy them to other parts of the battlefield for maximum effect. At the same time, he also delegated more authority to the commanders of large units, known as divisions. By having more independence, these large formations could split themselves up so as to use more roads simultaneously when marching, increasing the speed of Napoleon's armies. In the near-term, this gave him more flexibility in re-deploying his forces than the other generals he faced. But in terms of its significance for warfare writ large, these were a series of important steps towards maneuver warfare which we will discuss later on.

Napoleon also took the next logical steps in terms of concentration of forces. Napoleon understood that if you could break an enemy's formation at one or more points in their line, that would enable you to potentially envelop or encircle their formations to achieve victory. As a former artillery officer, Napoleon understood the potential for artillery to shock enemy troops, a capability he deployed to great effect by concentrating artillery fire at certain points in the line. He also made extensive use of columns as attacking formations, rather than lines. This is a bit hard to describe purely as audio and unfortunately I couldn’t find any great diagrams to detail it, but here goes. Imagine you are facing enemy troops lined up in two rows of 100 men each. Instead of you lining up the same way, you line up in two rows of 10, or twenty men each. Your line is now much narrower, but deeper. In fact you're no longer in a line you're in a column, at least from the enemy's perspective. If you can pierce the enemy's line in this column formation, all of a sudden you have rendered all of the soldiers at the ends of the enemy's line useless, because they are facing the wrong way. Like I said, a bit hard to describe, but take my word for it that Napoleon used this and other ideas to great effect. As I said, concentration of forces was an idea that Napoleon moved along rather than invented, but I felt his contributions were important and worth covering.

This is certainly not an exhaustive list of the changes that occurred in the conduct of warfare during the Napoleonic era, I've left out naval conflict entirely for example. But I think we've hit the most significant: the transition to warfare by entire nations, military reorganization to enable more flexibility and increased emphasis on the concentration of not just forces, but artillery firepower. The next big change tracks with the Industrial Revolution which took place over the course of the 19th century and saw the massive mechanization of economies for the first time. When I think about the impact of industrialization on warfare, I think about three major changes: much more dangerous weapons, especially artillery but automatic weapons as well; much more ammunition to feed those weapons; and the acceleration of warfare at the strategic level due to the arrival of railroads.

Let's start with the change in weapons themselves. During the Napoleonic Wars, artillery size was constrained by the technology available for actually casting cannons. The largest artillery pieces widely fielded by the French Army during this period fired a 12 pound shot and had a range of roughly a kilometer. At the outbreak of World War 1, the standard issue field artillery piece for the British Army fired an 18 pound shot with an effective range out to 6 kilometers. So to be clear, a 50% increase in shot weight and a 6x increase in range. Pretty substantial in the space of 100 years. But to really drive this point home, I actually want to take a quick jump ahead in time to World War 2 and take a quick side quest to talk about the largest artillery piece ever built, just so you can understand how far industrialization enabled military engineers to push the development of artillery.

In the Second World War, the Germany Army fielded two guns named the Schwerer Gustav which is German for Heavy Gustav. I still find the scale of this thing a bit difficult to comprehend. It's the kind of thing you don't think you can wrap your mind around unless you see it for itself but both units were destroyed during the war. For a start the Heavy Gustav was among a class of artillery called railway guns because, you guessed it, they travelled on railways. They were too heavy to be moved any other way. But a single railway was not enough for the heavy Gustav, it required twin sets of tracks which, given that the fully assembled gun weighted over 1,300 tons, had to be manufactured with reinforced steel. The barrel could only be moved up and down to control elevation. To move the gun's range side to side, the twin sets of railway tracks had to be built with curvature - that's how the gun was aimed.

In terms of capabilities, this thing had an effective range of over 39 kilometers, firing shells weighing upwards of 7 tons, with the ability to pierce up to seven meters of concrete. In terms of weight, a big family SUV probably weights somewhere between 2.5 to 3 tons. So this thing was firing just over two of those nearly 40 kilometers. I've included a photo below so you can get a sense for the scale of this thing, and you can see clearly the twin tracks I was referring to.

So artillery got deadlier, but you also had the arrival en mass of automatic weapons. These proved extremely problematic in the First World War and were one of the reasons that conflict devolved into trench warfare. Running at the enemy across open ground and being mowed down by machine guns made attacking head on extremely costly in terms of manpower, hence the reliance on trenches.

Now let's talk about ammunition. Again the comparisons between the Napoleonic era and World War 1 is the most instructive here. At Waterloo, Napoleon's final battle where he was defeated by the combined European powers, he is estimated to have had approximately 20,000 rounds of artillery ammunition available to him. In 1916, ahead of the Battle of the Somme which was an Allied offensive against the Germans, the British stockpiled just shy of 3 million artillery rounds. These are not precisely apples-to-apples numbers because the Somme offensive took place over several months. But I think you get a sense for how much industrial capacity had increased. Also just given that these are very precise numbers, if you want to check them I am getting them from John Keegan's 1976 book, The Face of Battle.

Ok so guns got bigger and deadlier, and they had more ammunition to fire. Not a great combination for soldiers fighting battles… Let’s talk about how industrialization impacted logistics and speed in warfare. The big change here was the arrival of railways. Railways significantly increased the speed with which large quantities of men and materials could be moved long distances. This had a number of downstream impacts. One is that it opened up new strategic options. For example prior to the First World War the German Army developed something called the Schlieffen Plan. According to this plan, if war broke out in Europe, Germany aimed to defeat France first in a quick strike around French lines. Germany would then transfer its forces across the continent, using railways, to confront Russia.

This higher speed of strategic movement introduced instability in the security arrangements between countries. Because railways meant that one country could put tens of thousands of men on an enemy’s border in a day, the speed with which a country mobilized was thought to be potentially critical in determining the outcome of a war: if Country A mobilized its troops faster than Country B, Country B would lose. This perception guided much of the decision making that led to World War 1. The countries involved felt they had to declare war quickly lest their adversary declare war and mobilize faster.

Alright now we've covered the 19th century and the role of industrialization, let's get into the 20th and early 21st centuries. During this period we had a big doctrinal change in warfare, as well as important technological changes. Let's start with doctrine. Up until the early 20th century, warfare was mostly about attrition which is another word for killing the enemy. Whichever side killed the most of their adversary, won. Starting late in World War 1, and throughout World War 2, we saw a new strategic and operational emphasis on maneuver. The most famous example of this is, of course, the blitzkrieg tactics of the German Wehrmacht, the German army in the Second World War. Rather than attacking France head on through its entrenched positions behind a series of fortifications known as the Maginot Line, the Wehrmacht maneuvered around the French army and the British Expeditionary Force via Belgium, and France ended up falling in six weeks.

Killing the enemy didn't go away as a fundamental aspect of warfare. Instead what the German army demonstrated was that movement could achieve fighting positions that left the enemy with no choice but to surrender or die. And if you recall our discussion about Ukraine, this theme will be familiar. Ukraine's Western allies pushed a maneuver-centric concept on Ukraine for prosecuting its summer 2023 counteroffensive: achieve a break in the Russian lines that would enable mechanized and motorized Ukrainian units to operate in Russian rear areas, destroying logistics and encircling Russian units.

So that's the doctrinal change. In terms of technological change, the arrival of airpower was a big one. While planes were used in World War One, their potential impact on warfare really came through in the Second World War. Most important was the tactical application of air power against land and sea targets. On land, the Germans used dive bombers to destroy enemy tanks and strafe infantry formations. At sea, aircraft put an end to the battleship forever. In December of 1941, the Japanese Navy sunk the HMS Prince of Wales, the pride of the Royal Navy, using carrier based aircraft dropping torpedoes. Overnight the aircraft carrier, not the battleship, became the most important power projection platform on the ocean.

There's a whole separate conversation to be had about strategic bombing, its effectiveness and its morality. But I'm going to table that for now because I want to focus on conflict between armed forces.

Going along with airpower was the development of precision-guided munitions. Using GPS, these were bombs that had error radii of a few meters rather than 100 meters or more for a typical gravity bomb or dumb bomb. During the First Gulf War, the world marveled at bombs that could be dropped through air vents or windows to target specific buildings. Precision guidance was also paired with missiles which further extended the range of precision strike over traditional, ballistic artillery. We love side quests here so here's another one: GPS was developed by the US Department of Defense. In 1983, President Reagan ordered that it be made available for civilian use after a Korean Airlines plane flying from New York to Seoul, via Anchorage, drifted into Soviet airspace. The Soviets thought it was a spy plane and shot it down using air-to-air missiles. Reagan subsequently made GPS available for civilian use to ensure such an incident never happened again. The Soviet Union admitted to shooting the plane down, but hid behind the spy plane accusation. It was only after the Soviet Union collapsed and the flight recorders, which the Soviet Union had been able to recover, were made available that the country acknowledged its mistake.

Alright folks. Is anyone still there? Anybody at all? If you are, you made it. Well, you made it to basecamp. We've finally reached the end of my attempt to briefly recap the major developments in the history of warfare and now we find ourselves able to turn to the question of what the future of warfare might look like. I think you can pick out a couple of consistent trends looking back over the history we just discussed. First, you have ever increasing professionalization and specialization among soldiers. From Gustavus Adolphus requiring his soldiers to march in a line, to today when militaries comprise not just infantrymen but pilots, sailors, doctors, mechanics, logisticians, and on and on. There are constantly new military disciplines emerging and being honed to a fine edge.

Second, the lethality of weapons is always increasing. Not only because they can deliver bigger booms, but because their precision has also risen ever higher. This has made force protection more and more important. An army that tried to fight in the Napoleonic style today would be vaporized in seconds on a modern battlefield. And so today military forces fight with much more dispersion, to reduce the impact of artillery and airpower.

Third, the speed of warfare is constantly going up. For centuries, armies were limited to the pace of foot and horse. Then railways arrived. Soon afterward came trucks and tanks. Then aircraft accelerated things still further.

Fourth, to support all of this has required more and more complexity in the logistics chain. The pointy end of military power has never been more dangerous. But that lethality has never been more exposed to all the enabling capabilities supporting it.

These all seem like quite durable trends for me. So when thinking about the future of warfare, the question is how do these trends extend, and how do they interact with new developments? And, furthermore, what can the war in Ukraine tell us about all of this?

Staying on the topic of continuity, the importance of territory, of actually physically taking and holding ground, looks set to continue. And the reason for that is, as the Prussian military theorist Carl von Clausewitz wrote, war is politics by other means. Military force enables countries to achieve their political ends by putting them in a position to compel the behavior of their adversary. Russia, despite years of modernization and military investment, still had to invade Ukraine in pursuit of its political objectives. And, on the flip side, the increasingly trench-based warfare of that conflict, which at times looks more like World War One than a 21st century conflict, shows that there's no substitute for soil.

I think what will happen though is that defensive positions and the distance between opposing lines will continue to grow and grow. During World War 1, the distance between Allied and German trenches was less than 100 meters in some places. I could not find concrete comparable data for the war in Ukraine, but I am confident that in general the distances are greater due to the longer reach of precision strike. And I think if you follow the trend lines we've been talking about, these distances will continue to grow and grow.

At the same time, I think forces will seek more and more ways to achieve dispersion as a way of blunting the impact of ever more lethal precision strike. This will mean more reliance on communications to keep smaller and smaller units in contact with one another. But it will also increase the returns to training and doctrine. The more that units can act as a cohesive whole without having to explicitly communicate, the better off they will be, but that will be increasingly harder to pull off as units maneuver at greater range from one another. This will in turn create new vulnerabilities in terms of greater reliance on wireless infrastructure. To that end, I think more and more militaries will explore a concept known as mesh networking. A mesh network is one in which all of the devices in the network itself act as transmission points. Imagine a group of mobile phones that are all able to connect with each other. Mesh networks are highly resilient because the loss of one unit does not bring the entire network down.

Staying with the theme of technology and attempts to dull the edge of artillery and other precision weapons, I anticipate growing interest in stealth technologies and materials science. One of the constant challenges both sides have had to contend with in Ukraine is the persistent surveillance of the battlefield by drones. It is virtually impossible to move undetected for very long. Then, once identified by the enemy, you either become a target for a drone or artillery strike. This seems especially problematic at night when human soldiers show up bright white against the colder ground when using infrared.

To counteract this is going to require more investment in stealth. While the value of this capability is already heavily invested in among air forces, it is less the case for ground forces. But clearly it is going to be required for militaries that intend to pursue maneuver-based doctrines. At night, materials that are able to make a soldier's heat signature appear to match the background temperature will be the focus, while in the day time new camouflage technologies to obscure movement will be important.

This is of course a good jumping off point to the topic of drones generally. The very earliest "drones" date all the way back to World War 1 when remote controlled planes were used for target practice, and the technology has been in refinement ever since. The use of the Predator and Reaper in the Global War on Terror was when they really entered the public consciousness but now they've taken an even further leap, especially the first person view drones.

A lot of people have speculated whether drones, when paired with AI which I will cover separately, will bring in a future of cheap swarms of machines rather than a reliance on big, expensive platforms. There is no doubt that this seems like the conventional thinking on the future of warfare. More investment in smaller, more disposable weapons platforms that can overwhelm the enemy with sheer numbers. As a logical development, I see a lot of merit in it and I'm tempted by it.

But increasingly, I suspect things will go the other way. Because, again turning to history, the number of times military engineers and designers have opted for smaller, simpler systems is never, as far as I can recall? If you think about the evolution of naval power, once sailing ships were found to be suitable to hold cannons, countries started building massive, three deck ships of the line capable of holding over 100 guns. The arrival of coal-driven boilers and steel gave us the huge dreadnaughts and battleships of the early 20th century. Then the aircraft carrier arrived and it was considered so valuable, an entire fleet concept had to be designed to supply and protect it: the carrier strike group.

There are some sensible push backs here. The first is that drones can be controlled remotely, and that increasingly they are autonomous, and can be left to their own devices with AI direction. I have two problems with this argument. The first is that it is not clear to me why autonomy should necessarily lend itself to favoring a swarm approach? Like, if you buy my historical characterization that military weapons systems tend toward the ever more complex, why not just have one big autonomous drone then?

That's the first objection. The second objection I have is that autonomy, in the very abstract sense, has never really been the problem when it comes to command and control of individual pieces of machinery on the battlefield. And what I mean is, nations have always been able to find enough people willing to die to pilot or control individual machines. Consider the kamikaze pilots of World War 2. These were Japanese fighter pilots who, towards the end of the war, were commanded to fly their planes directly into American ships. I guess another way of saying this is that the "swarm" concept has never been gated by humanity's capacity to put individual thought into individual machines.

Related to all of this, but somewhat adjacent, is a more general argument about big systems vs. dispersed systems. I.e., there's a debate that's effectively upstream of autonomous swarms which has the form of: are you better off having one big super tank, or lots of cheaper but less effective tanks? Towards the end of the Second World War, these were two divergent paths taken by the Allies and the Germans. The US mass produced thousands of Sherman tanks which were, in a word "fine". While the Germans increasingly opted for incredibly modern, effective models like the Tiger and the Panther, but were unable to produce them in sufficient numbers to achieve a decisive impact on the battlefield.

People often look at that situation and conclude well, the Shermans won. But to me it seems to be more a story of industrial capacity than positive proof that more, cheaper weapons systems are better? Perhaps the US should have copied the Tiger design and started producing them as well? Another oft-discussed example in this debate is the aircraft carrier, which I mentioned earlier. The USS Gerald Ford, the most recent class of carrier built by the United States, cost somewhere in the neighborhood of $13 billion to build. And you will often hear people point out that it could be sunk with torpedoes and missiles costing a few million dollars.

The US Navy understands this. Like, hundreds of thoughtful flag officers have gone through programs at the US Naval War College in Rhode Island and had time to ponder this issue and to do the sums. And you know what they ended up concluding? They concluded that airpower at sea is so critical, and so dominant that you must have a super carrier to carry it and instead of trying to make cheap, less expensive carriers what you have to do is build an entire fleet around the carrier whose job it is to protect the carrier. I mentioned this earlier, the carrier strike group. And it's worth just briefly describing this formation so you can understand just how convinced the US Navy is that, for lack of a better phrase, this is the way. A CSG goes to sea with the carrier, obviously. It also has one or two guided missile cruisers that fire long range missiles. Two to three guided missile destroyers which provide anti-aircraft and anti-submarine protection, up to two attack submarines, and then a whole collection of supply and logistics ships.

And, by the way, it is not just the US Navy who thinks this is the right way to go. The Chinese navy thinks the same thing and is actively building domestic carriers which it will inevitably have to protect and escort in the same fashion as American carriers.

Now, of course, you might point out that both the US and Chinese navies could be wrong and their reliance on these huge platforms will be a vulnerability in a major conflict. And you might be right. But my point is that military thinkers seem to always lean toward the bigger, more capable platform.

Ok so if you buy my view that there is this tendency towards big, complex systems what does that mean for drones? Personally, I think we will see a lot of today's concepts replicated in drone form. Why not a large underwater drone equipped not just with long range missiles, but a drone swarm of its own? Or drones launched from the air by a "mother ship" drone? I think when you take out crew requirements from large, platform-like pieces of hardware like carriers, submarines, tanks, fighter aircraft and so on, the temptation to fill the saved space with new capability is going to be significant, and that's what military engineers are going to do.

This is a great jumping off point to talk about AI and, separate from drones, true autonomy in weapon's platforms. Killer robots are often presented in dystopian terms. The Terminator series of films inevitably comes up. I think this is unfortunate because putting aside the fact that warfare is an inhumane activity, I actually think we're better off with robots in lots of cases. Robots do not get tired and they don't develop psychological trauma. And both of those are factors or causes for a lot of the crimes we see in war. Of course, the implicit assumption I'm making here is autonomy guided by liberal values with respect to war of the kind someone like a Michael Walzer might espouse. I suppose on the morality front the way to think about it is that robots will probably make cruel militaries more cruel, and militaries that are aspiring to some form of justice, more just.

I realize now that the question of ethics is really a sidetrack from what I'm supposed to be talking about which is how will AI and automation impact warfare. I think what AI will do is to take away from humans a lot of the most dull work in warfare. Guard duty, for example. Maintaining defensive positions actually takes a big toll on soldiers. It's boring. But you're still in danger because you're on the front line. That's very psychologically demanding. But it's something AI can do instead, or at least with which it can assist.

I thought about going on a technical detour to explain how and why I think AI will be able to do this but I decided against it because boy, have we been going for a while. So you will just have to take my word for it that I am convinced that current models can do things like distinguish between a deer, and a soldier. And they can definitely distinguish between a city and a military base. So you'll see lots of dull, boring jobs turned over to AI.

What does this mean for the conduct of warfare though? I think what it means is that actual combat will increase in intensity. And the reason for this is if you take away a lot of the cognitive and physically draining activities warfare requires of soldiers away from them, that gives them more time to rest, recuperate, train and plan. Which in turn means when they do launch into actual battle, it is going to be of a higher intensity than it might otherwise have been if rest times were shorter.

And what about when these assaults actually take place? Are we going to see AI-enabled, humanoid robots marching alongside human brethren? Or in their place? I’m pessimistic about the prospect for this kind of future, at least given the current paradigm behind AI. Again, avoiding the technical detour, the technical framework that powers the large language models like ChatGPT is inherently probabilistic. As a soldier, I think that's going to make you very, very nervous about how an AI-enabled robot is going to behave in combat. You might be willing to have it along to carry ammunition, conduct surveillance and alert you to threats. But not to carry a weapon. That doesn't mean we might not get AI-enabled drones operating on their own, separate from human soldiers. But I don't see intermingling as very likely in the foreseeable future.

One last quick hit because it's a big topic I haven't touched in depth: cyber. My sense is that cyber's main role in warfare will be on the home front: disrupting enemy infrastructure and economic capacity. I think there's pretty clear eyed recognition among modern militaries that they cannot leave their hardware vulnerable to enemy hacking and so they're both trying to harden their supply chains, but also ensure they continue to train to be able to fight without such a heavy reliance on technology.

So, in a vain attempt to bring all of this together, I think what this means is that the next phase of warfare's evolution is going to involve even more dispersion between forces, a necessity brought about by the need to avoid ever more lethal strike capabilities. Those forces will have to rely on new technologies to conduct offensive operations including stealth and new, more resilient communications architecture. And when they do give battle, they will do so with greater intensity because AI and robots are doing more of the heavy lifting. In parallel to all of this will be the emergence of new weapons platforms that are either remotely piloted or autonomous.

Ok, whew. That brings us to the of what I think is comfortably the longest episode I have ever recorded. And this is what you were promised! Less frequency but more depth. I hope you found it enjoyable. As always thanks for listening and don't forget to submit requests - it turns out you may get them answered!

CWI #39 - The future of warfare and some Ukraine